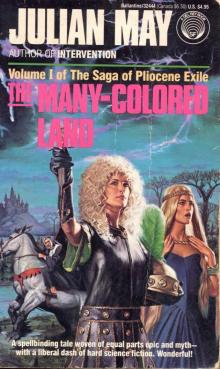

The Many-Coloured Land

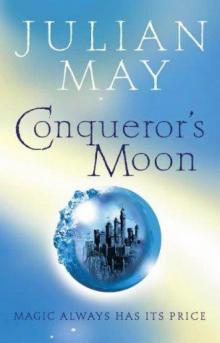

The Many-Coloured Land Conqueror's Moon

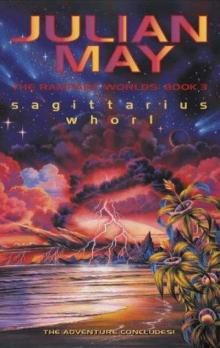

Conqueror's Moon The Sagittarius Whorl

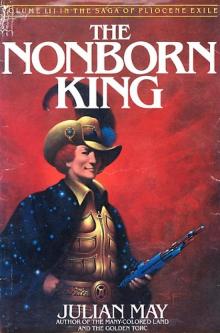

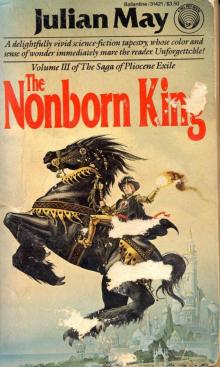

The Sagittarius Whorl The Nonborn King

The Nonborn King Sky Trillium

Sky Trillium The Sagittarius Whorl: Book Three of the Rampart Worlds Trilogy

The Sagittarius Whorl: Book Three of the Rampart Worlds Trilogy Intervention

Intervention Orion Arm

Orion Arm Diamond Mask

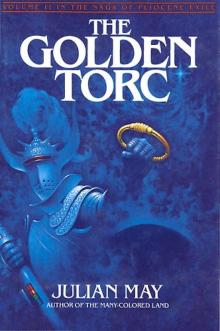

Diamond Mask The Golden Torc

The Golden Torc The Noborn King

The Noborn King Magnificat

Magnificat Jack the Bodiless

Jack the Bodiless Perseus Spur

Perseus Spur The Adversary

The Adversary Sorcerer's Moon

Sorcerer's Moon Sagittarius Whorl

Sagittarius Whorl The Intervention (Omnibus)

The Intervention (Omnibus) Magnificat (Galactic Milieu Trilogy)

Magnificat (Galactic Milieu Trilogy) Jack the Bodiless (Galactic Milieu Trilogy)

Jack the Bodiless (Galactic Milieu Trilogy) Diamond Mask (Galactic Milieu Trilogy)

Diamond Mask (Galactic Milieu Trilogy) The Many-Coloured Land sope-1

The Many-Coloured Land sope-1